- Home

- Sara Gruen

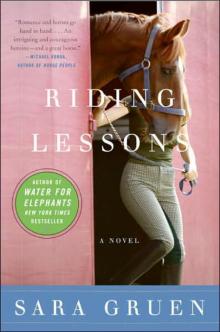

Riding Lessons Page 6

Riding Lessons Read online

Page 6

I thought that vigilance would act as insurance, and protect us and her from the perils of the teenage years. But how vigilant could I have been if she could get a tattoo?

I close the door to my room, and sit at the little table by the window. With shaking hands, I reconnect to the Internet, determined to find a surgeon who will see us now, today.

It is not the tattoo that frightens me so much--I hate the tattoo, the tattoo is coming off--but that's not what frightens me. What frightens me is that I didn't know about it. And if I didn't know about that, what else don't I know about?

Twenty minutes later, I descend the stairs clutching a piece of paper. I come down shouting, not even knowing if anyone else is still in the house.

"Eva! Eva, where are you?"

I pause at the bottom of the stairs, listening for signs of life.

"Eva! Get out here!"

At first, I think the house is empty. Then I hear a motor whirring and when I turn around, Pappa appears in the doorway of the living room. Sickness washes over me.

"They've gone out," he says.

"What do you mean?" I ask, staring at my father.

"Your mother took her to the grocery."

I stand with a quivering jaw. Then I explode. "Mutti had no right to take her anywhere. Eva is my daughter. We have an appointment with a plastic surgeon in half an hour. I need her here now."

I stare at my frail father, waiting for him to defend Mutti. I almost wish he would, because I need the release of an argument. But he doesn't.

I burst into tears.

After a few seconds I hear the motor whirring again, and then Pappa pulls up next to me. With great effort, he raises his hand to mine. When I feel the back of it against my fingers, his skin as fragile as crepe paper, I sink to the floor and lay my head on his knee. It feels like nothing but cloth-covered bone.

"Oh, God, Pappa. Why? Why would anyone with skin as beautiful as that have a goddamned unicorn tattooed on it?"

"She was angry about the stud."

"What?" I say, raising my head.

"She was angry about the tongue stud, so she got the tattoo."

I stare at him in horror, and then drop my head back onto his leg. A moment later, his hand is on my head, light as a sparrow. He strokes my hair.

"I know you're upset, Annemarie. It's a shock, I know. But don't get into a state. No, it shouldn't be possible for someone her age to get a tattoo, but it does seem to be the fashion these days."

"But Pappa! It's going to cost a fortune to get it removed. And it will probably leave a scar. I just can't--"

"Hush, Annemarie," says Pappa, continuing to stroke my hair. "Think about it. She got it because of the tongue stud. If you force her to remove the tattoo, who's to say she won't get another one? A bigger one, in a more visible place? Or pierce something else?"

I frown against his leg, but say nothing.

"Better to let her keep it," he continues. "For now. Who knows? Maybe when she matures she'll get sick of it and have it removed. And then you can say, 'I told you so,' mein Schatzlein."

I lift my head and look into his face. He hasn't called me that in years.

I am my parents' greatest disappointment in life, which is made worse by the fact that at one point I was their greatest hope. Oh, I suppose all children are their parents' greatest hope, but this was different. I excelled at the one thing my parents devoted their entire lives to--was doing Grand Prix work by the age of sixteen. When it became apparent that I really was a world-class talent, my father and I traveled all over Germany, France, and Portugal looking for the right horse, although in the end we found him in South Carolina. I knew he was the one the moment I laid eyes on him--hadn't even ridden him yet. I just looked at his powerful red and white limbs and the way he held himself and knew, and Pappa trusted my instinct. Not to mention Harry's pedigree and considerable career to date.

Eight months after he arrived from South Carolina, we packed up again, and this time both of us went off to train with Marjory. From that moment on, we were unstoppable. Until the accident.

I knew from the very beginning that I would never get on another horse, although I never made a declaration. In the early days, there seemed little point.

However, even when my nerves began to get reacquainted and the idea of becoming whole again stopped feeling like a hopeless dream, I still neglected to tell my parents. I stayed silent even as they were making plans for my triumphant return.

They started planting issues of Eventers Monthly and Sport Horse Illustrated around the house. I'd go into the kitchen and find one on the table, open at an advertisement for a particularly promising eventer, some massively strong Hanoverian or Dutch Warm-blood. Next time, it would be on the hall table, or my dresser. I would look at the ad, and then close the magazine, leaving it where it was. It didn't matter how many times I did this. The next day, the next week, there would be another, followed by another, followed by another, until I got to the point where I was closing the magazine without even looking at the horse.

When my parents found out I was leaving New Hampshire and had no immediate plans for doing anything with my life beyond being a wife, it caused a rift so deep that it still hasn't healed. But as upset as Pappa was, it was Mutti who became openly hostile. She believes I broke Pappa's heart, and maybe I did.

There's no question I could have had a career in riding, even if in reduced form. I could have become a trainer. I could have taken my place beside Pappa and made this a family enterprise.

But I didn't. I ended the family dream unilaterally, and although neither parent ever came out and said that, every word they didn't say was designed to remind me of it.

It seems perfectly natural, then, that Eva, Mutti, and Pappa are watching television in the living room without me. Mutti and Eva are curled up on the couch, and Pappa is parked at the end. The three of them are sharing a bowl of popcorn, thick as thieves.

I stand watching them for a moment, carefully staying out of sight. I'd like to join them, but can't bring myself to do it. My legs don't want to walk into the room.

Instead, I slink off to call Roger.

A woman answers--Sonja, I assume--and I am frozen. I should have expected this, but somehow I didn't. I pause with my mouth open, and then slam the receiver down, holding it there with both hands as though it might otherwise leap up. Then I bring my hands to my face and hyperventilate between my fingers.

A minute later, I call back. This time, Roger answers.

"Goddamn it, Annemarie! Where have you been? I've been trying to get in touch with you for ages. Why haven't you returned my phone calls?"

I am stunned into silence. Roger doesn't get mad. That's one of my complaints about him. There's never been an ounce of passion in him--I never could get a rise out of him, even when I was pitching for a fight.

"I didn't get your messages," I say. "I'm in New Hampshire."

"Oh," he says, sounding perplexed. "Is everything all right?"

"No, actually, it's not. My father has ALS."

"Oh, God, Annemarie. I'm so sorry. I had no idea."

"No, how could you?" I say.

There's an awkward pause as he gropes for something to say. He has never been close to my parents, partly because they never liked him and partly because of my relationship with them, but still, he must be shocked.

"I'm so sorry. I really am. Look, I don't mean to be insensitive, but when will you be back? I need to talk to you," he says.

"I won't be."

"Pardon?" he says.

"We're not coming back. We're staying here."

"What are you talking about?"

"We're staying here. Eva and I are staying here."

For the second time, Roger explodes. "You can't do that! Annemarie, she's my daughter, too--you can't just take her to another state!"

"I have and I did," I say. "And anyway, we agreed to sell the house."

"Yes, but you never said anything about leaving town. Annemari

e," he says, shifting gears. "Please be reasonable. Can we please talk about this?"

"What's to talk about? Oh, but I forgot," I say. "Apparently there is something you need to tell me."

"Annemarie--"

"I'm not coming back, and I doubt very much you want to try to force Eva into living with you, so you might as well just tell me whatever it is you want to tell me about and be done with it."

A pause. "I need to see you."

"Why? So you can tell me you're going to marry Sonja? Spare me."

He is silent for so long I wonder if he's gone off the line. Then he speaks. "Please look at the settlement. We can talk when you come back for the hearing."

"Fine," I say, deciding not to tell him that I won't be back for the hearing. Besides, unless his news is that he's leaving Sonja, there's nothing I want to talk to him about.

"Annemarie?"

"What?"

"Could you please put Eva on the phone?"

"Eva," I shout without bothering to cover the mouthpiece. "Do you want to speak to your father?"

I extend my arm, holding the phone toward the doorway.

"No," she shouts back, right on cue.

"You heard her," I say to Roger.

He sighs. "Look Annemarie, I'm not pretending that you don't have a right to be upset with me--and I mean, really, really angry. But please, for Eva's sake, don't foster that in her. It can only hurt her in the long run."

"Whatever. Fine," I say. And then I hang up, because I'm angry with him for being right.

The day after Roger left me, Eva returned from Lacey's, unaware that against all odds, her father's transgression had eclipsed hers.

When I told her what had transpired, she blamed me, bursting into tears and screaming that if I hadn't been such a bitch all these years he probably wouldn't have left at all. Then she retreated to her room, amidst great stomping and slamming of doors.

When Roger called later that day to give me the address of the place where he was staying, I thanked him and told him I would give it to my lawyer. Of course, I didn't actually have a lawyer, because I still thought he was going to return, but I wanted to make a point. I wanted to let him know he shouldn't wait too long to come to his senses, because there was no guarantee that I'd still be around. Then he asked to speak to Eva.

As I handed her the phone, her face clouded over like that of a baby gathering breath to scream. Before he even had time to say hello, she started shrieking, "Fuck you! Fuck you! Fuck you! Fuck you!" And then she hung up. She hasn't spoken to him since.

I was horrified, and not for Roger's sake. Eva's been on a slow slide for a while, and I'm beginning to believe her very future is at stake.

Chapter 6

The next morning, the four of us pile into the van and head for the rescue center.

Perhaps "pile into" is not the right phrase. Even though technology has changed considerably over the last twenty years, getting Pappa into the van is a long process: first, Mutti slides the door open and extracts a box with controls. Then she presses a switch that unfolds the hydraulic lift, and then another that lowers it to the ground. At that point Pappa drives onto it, and she reverses the process. After he maneuvers his chair so that he's facing the windshield, she applies clamps to his wheels so that he is secured to the floor. Then, finally, we're on our way.

The whole process has left me sick to my stomach, although I'm not sure whether it's caused by my inability to face what's happening to Pappa or the prospect of seeing Dan again.

I am more nervous than I thought I would be--how will I greet him? Is twenty years enough time to assume that he has forgiven me? Should I hug him? Shake his hand? Be friendly and effusive, or formal and reserved?

I worry about this until the moment I see him emerge from the doorway of the stable, tall and muscular, the epitome of American masculinity in his jeans and flannel shirt. He stops at the sight of me, and then recovers almost instantly.

"Annemarie," he says warmly. "You look wonderful." He strides forward, takes my right hand in both of his, and kisses me on the cheek. For some reason, I'm suddenly in danger of crying.

"Thank you. So do you," I say. And he does. He looks fantastic. His sandy hair has some gray in it, and his features are a little coarser, but I swear he's as handsome as the day I first clapped eyes on him. I am embarrassed, wishing I'd taken a little more trouble with myself this morning. I also wonder how much he knows about the current state of my life.

"Anton, good to see you," says Dan, turning to Pappa and taking his hand. Then he turns and kisses Mutti on both cheeks. As he takes her hand, I see that her fingers curl around his, that her lips make actual contact with his cheek. I think back to my air hug at the airport.

"And you must be Annemarie's daughter," he says, turning to Eva and smiling broadly. He extends his hand.

"Yes," she says suspiciously. After an embarrassingly long pause, she takes his hand.

"You're as pretty as your mother," he says, and her face hardens perceptibly. It was the wrong thing to say, but he can't have known that. He doesn't know that any comparison to me is an insult of the most enormous proportions.

"So where is this horse, and what's so special that we had to come all the way out to see him?" says Pappa. He sounds curt, and I turn to him, embarrassed by his temper. But Pappa is smiling. Dan laughs immediately--doesn't misread him for an instant--and again, I feel a jolt of jealousy. But why shouldn't they be close to Dan? It's not as if I've been around.

"He's in the quarantine barn. And I think I'd like you to see for yourself."

Dan leads us around the main barn and heads for a concrete building a good distance away.

I follow Pappa, and watching him cross the gravel is almost more than I can take. His head bobs dangerously, as though there's barely any strength left in his neck, and I suppose there isn't.

And then I look over at Mutti, at her wiry little Austrian frame marching purposefully along with my daughter, and I'm angry at her. Angry that she didn't tell me how far the ALS had progressed, for not giving me some warning. For not telling me sooner, although I don't know what I would have done differently. With a husband and a job, I could not have come back--would not have wanted to.

"Oh, damn. Judy's got a horse in the aisle," Dan says, peering into the doorway. "These guys just came from auction and are pretty riled up. I don't want you in the aisle, Anton. It's too dangerous. Why don't you all go around to the right--there's a paddock there. I'll let him out the chute."

I am shocked at how easily Dan refers to my father's helplessness, when I--his daughter--cannot decide whether to acknowledge it or pretend it's not happening at all. I look at Pappa quickly to gauge his reaction, but he is motoring around the side of the building. I follow, jogging a little to catch up, and the four of us line up by the fence.

A minute later, Dan slides the door of the chute open. He's got a rope looped over his arm, and after checking to see that we're all here, advances a couple of steps into the opening, flapping the rope in front of him.

"Hiyah!" he yells. "Hiyah!"

A second later, he leaps onto the second railing of the fence as a horse explodes from the building.

I catch my breath, because I see what he is immediately, even as he's still a whir of motion, a blur of emaciated frame barreling around the edge of the fence.

"Mein Gott in Himmel," says Mutti.

The horse comes to a stop across the paddock and stands with his left side to us, flanks heaving, eyeing us warily.

I clap a hand over my mouth, afraid I might cry out.

It is Harry. It is Harry. It is starving, it is mangy, and it is lame, but it is Harry. My knees feel like they're going to buckle.

"Wow, what a weird horse," says my daughter.

"No, Eva," says Dan's voice from behind me. He has come back through the barn, and is standing so close I can feel his breath on my hair as he speaks. "That's a liver chestnut with white brindling. One in a billion. You're lucky if you

see one of those in your lifetime. Never mind two."

In coloring, the horse could have been Harry's twin. The same deep red, the color of dried blood, from foot to forelock, run through evenly with white stripes. Absurdly gorgeous, and gorgeously absurd.

"Where on earth did you find him?" asks Pappa.

"In the kill pen."

"What?" says Eva. She turns sharply, her face poised for outrage.

"At the auction," says Dan. "I saw him in the kill pen, and, well, I had to get him. Obviously."

"Where did he come from?" asks Mutti.

"Who knows? He came in with a shipment from Mexico, and before that, we can't trace him. You know what these auctions are like--the horses' histories are the last things on these people's minds. My scanner didn't pick up a chip, either. But there's no real reason to think he's valuable. He's a mess. It's just that with his markings..." He looks over at me quickly, apologetically, and then lets the sentence go unfinished.

"Why was he in the kill pen?" I ask. I still can't take my eyes off the horse. His condition is appalling: his hipbones are jutting, and his hooves are long and cracked, forcing his legs to bow at an unnatural angle. The top of his tail has been rubbed to the point of near baldness, and his mane is thin and ratty. He stands with his ears back, watching our every move. Then he paws at the ground, and drops his nose to rub it against his leg.

"Did you see how he came out of the chute? I had to sedate him to get him onto the trailer, and then again to get him out and into the stall."

"He doesn't look crazy now," I say, surprised at how indignant I sound. This is not Harry.

"What's the kill pen?" I hear Eva ask as I move away, following the outside of the fence. The horse keeps his eye on me, and as I round the fence, he turns, inch by inch, so that his left side is always facing me. By the time I get to the far side of the paddock, we're five yards apart.

I lean against the fence, watching his face. There's fear in his expression, although something else, too. I wish I could tell what was going on in that head of his. And what a head--even emaciated, it's lovely. Strong-boned but refined, with a hint of a Roman nose. Hanoverian, I'll bet. In fact, except for the small star, the face could be Harry's.

Ape House

Ape House Water for Elephants

Water for Elephants Riding Lessons

Riding Lessons At the Water's Edge

At the Water's Edge